|

Tweet

|

|

|

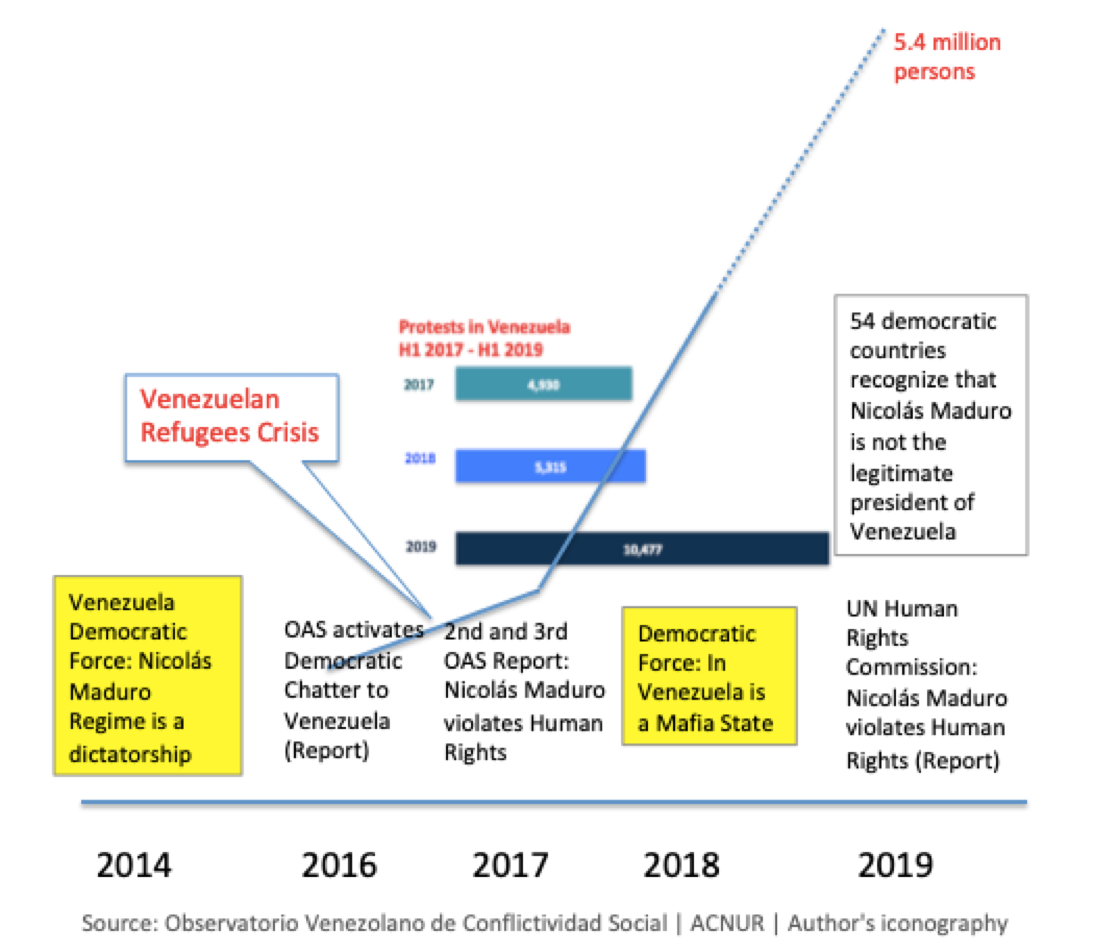

There is a huge time gap between what Venezuelans need and what the international community is doing to get to the solution to the Venezuelan crisis. Since 2014, a majority of Venezuelans have been trying to resolve the governance crisis in the Bolivarian country through a peaceful, democratic, and constitutional exit. Their struggle has been based on citizen pressure, mobilizations, and protests, all in democratic forms. Nicolás Maduro's response has been the criminalization of protests and repression. Between January 2014 and October 2017, 11,993 people had been arbitrarily detained, of which 62.4% were sentenced according to the October 2017 Criminal Forum report. Moreover, the Maduro regime has also tried Venezuelan civilians via the country's military jurisdiction. In 2014, food and medicine shortages, the high cost of living, citizen insecurity and the violation of human rights showed a substantial increase in the indicators of inflation, food and medicine scarcity, and crime rate for the previous ten years of the Chávez and Maduro governments. After Maduro's first year in Venezuela's presidency, 8 out of 10 Venezuelans saw his administration negatively, according to Datanalisis's poll. Before 2014, Venezuelan democratic voices, such as those of María Corina Machado, Antonio Ledezma, Leopoldo López and other leaders of the student movement, denounced to the democratic world that there was a dictatorship in Venezuela. But it was not until 2016 when Nicolás Maduro' government was recognized as an authoritarian regime which violated the main tenets of the Inter-American Democratic Charter. Organization of American States' Secretary General, Luis Almagro, invoked the OAS Democratic Charter for Venezuela in May 2017, opening a process that would lead to the suspension of the country. It was the first time that a multilateral organization wrote a report establishing the "violation of the constitutional order" and "the rupture of the democratic order" in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. The report recommended, among other measures: a recall referendum; the release of all political prisoners; a resolution to the medicine and food shortages; a stop to the permanent blockade to the National Assembly; the appointment of new members of the Supreme Court and the creation of an independent mechanism to fight corruption. Nothing happened - quite the opposite. Meanwhile, the international community continued to ignore the criticisms presented by the Venezuelan democratic forces about Maduro's illegitimate exercise of power within the framework of the rule of law. The reason for this delay in the international community's recognition of the authoritarian nature of the regime in Venezuela was associated with this idea that Venezuela had a "participatory democracy"; elections were held every year. Nicolás Maduro's claims that out "of 25 elections, we have won 23" during 20 years in power was enough to stop the international community in their tracks. In March and July 2017, the OAS Secretary General published two more reports assessing the status of Venezuela's democracy. In the latter, he pointed out the Maduro regime was an authoritarian regime that violated "human, political, social, economic and cultural rights". But, the international community continued to maintain its silence and indifference to the reality denounced by Almagro about Venezuela. However, a large proportion of Venezuelans has continued to protest to recover their rights and democracy. Others, confronted with a repressive State apparatus, have fled frightened, giving rise to the most significant exodus in the history of the Americas. They try to leave behind the hunger, misery, and the lack of opportunities. Regardless of this migration, in 2019 there has been an increase of 97% in social conflict as compared to the same period in 2018, and a 112% increase since 2017, according to the Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict. Also, the exodus is estimated to reach 5.4 million people, according to the OAS report on Venezuelan migrants and refugees. At the end of 2018, the Venezuelan democratic forces stated, for the first time, that the Maduro's dictatorial regime was changing into a mafia state that took control of much of the territory and most of the public sector institutions. Therefore, the situation in Venezuela should not be evaluated anymore as a political crisis only. The link between the Maduro regime with international gangs that deal with drugs, gold, coltan, diamonds, and human trafficking has internationalized the conflict. This year, 54 democratic countries do not recognize Nicolás Maduro as the legitimate president of Venezuela. They consider him an usurper. The governments of the United States, Canada, 14 Latin American countries and the European Union did not recognize the 2018 presidential election. Besides, on September 9, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, ratified that the Nicolás Maduro regime carries out extrajudicial executions and torture his adversaries for the period from January 2018 to May 2019. So, Bachelet's report confirmed the dictatorial nature of the Maduro regime. Therefore, it took five years (2014-2019) after Venezuelan democratic forces for the international community to recognize that there was a dictatorship in the country. Also, the diplomatic actions proposed to restore democracy in Venezuela have not been accepted, which include the establishment of an electoral roadmap to resolve the political crisis through the Oslo mechanism. The same thing happens with the measures proposed by the UN "to halt and remedy the grave violations of economic, social, civil, political, and cultural rights" in Venezuela. Maduro's dictatorship showed its real nature during these years, i.e., that it has become a mafia state. Hence, the mechanism to resolve the situation in Venezuela necessarily involves the use of international forces to fight the drug trafficking and the rest of illicit businesses, and to a lesser extent the employment of diplomatic means. If we were to estimate a similar learning curve for the international community as that of 2018 today, these countries would probably realize Venezuela is under a mafia state in 2022 or 2023. This is just too late. By then, the rule of law and freedom in Venezuela will already be too difficult to recover, and anarchy will reign. Therefore, the time to restore democracy in Venezuela is now. Otherwise, the exodus will further accelerate, and the majority of Venezuelans that stay in the country will be condemned to live in misery. The international community must immediately act in fighting Maduro's narco-state. There is no time to waste on Venezuela. |